For all of his use of Christian imagery, to the point of occasionally writing virtual Christian morality tales, Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen tended to avoid mentioning specific Christian holidays in his fairy tales. The young boy in “The Steadfast Tin Soldier,” for instance, receives his toys as a birthday present, not a Christmas one. Even the novella-length The Snow Queen, with its focus on winter and quotes from the Bible, never mentions Christmas at all.

Perhaps it’s as well, since his one major exception, “The Fir Tree,” may not exactly get readers into the holiday spirit.

“The Fir Tree” was originally published in New Fairy Tales, Second Collection (1844) next to another winter tale, The Snow Queen. It was swiftly overshadowed by that other story and Andersen’s other tales, but Andrew Lang reprinted a fairly faithful translation in The Pink Fairy Book (1897), and it can currently be found on multiple websites, in both fairly faithful and not really faithful translations.

As you might guess from the title, “The Fir Tree” is the story of a little fir tree who lives among several other fir trees, and desperately wants to be a big, grown up tree. We’ve all been there. His short size—not to mention the fact that rabbits can jump right over him—makes him desperately unhappy, and rather than enjoying life as a little tree, he spends his time envying the bigger trees.

This doesn’t decrease in the slightest when he sees these bigger trees cut down—off, he learns, for exciting adventures as ship masts (or so a bird explains) or as decorated Christmas trees. Suddenly the Fir Tree has something a bit unusual for a fir tree: ambition. Not to travel on a ship (though that does tempt him for a moment) but to be a beautifully decorated Christmas tree. He can think of nothing else, despite the advice from sunbeams and the wind to focus on youth and fresh air.

The very next Christmas he gets his wish. Getting cut down, it turns out, also brings quite a bit of sorrow—for the first time the Fir Tree realizes that he’s about to lose his friends and his home. Still! Christmas! As a splendid tree, the Fir Tree is swiftly selected by a family, and equally swiftly decorated—although even this doesn’t make him totally happy, since, well, the candles in the room and on the tree haven’t been lit, and he wants it to be evening, when everything will be splendid. Evening, though, turns out to be even worse, since once the tapers are lit, he’s afraid of moving and losing his ornaments—or getting burned. As Andersen gloomily tells us, it was really terrible.

Some relief comes when a very nice man tells the story of Humpty Dumpty, who fell down the stairs and married a princess—something that tree believes absolutely happened (after all, the man is very nice) and something he believes will happen to him. Unfortunately, he is instead dragged up to the attic, where he spends his time thinking about how lovely it was back in the forest and listening to stories, or trying to tell some mice and rats the story of his life and Humpty Dumpty. The rats are deeply unimpressed by the tree’s stories, and convince the mice to leave as well.

A few months later, the tree is dragged outside, chopped up, and burned.

HAPPY HOLIDAY SPIRIT EVERYONE!

It’s not at all difficult to see this at least in part as a metaphor for Andersen’s own life, one that started in poverty stricken circumstances before Andersen found himself brought to wealthier homes—to tell stories. Nor is it difficult to read the tale as another variation on Andersen’s frequent themes of “be careful what you wish for,” and “be content with what you have,” with the caution that trying to leave your surroundings, and wish for more, can lead to danger, misery and even death. Notably, the Andersen protagonists who do improve their fortunes tend to be the ones forced out of their homes (like the Ugly Duckling) or kidnapped from their homes (Thumbelina, though Thumbelina notably leaves a happy home and suffers for some time before improving her fortunes). The Andersen protagonists who want more from life tend to end up dead or worse.

Buy the Book

In An Absent Dream

And it’s also not difficult to read the tale as a comment on the often fleeting nature of fame. In its way, the Fir Tree is a performer, dressed up and pulled out on stage, playing a part, as Andersen notes. A background part, but a part. For one glorious night—and then it’s over. The Fir Tree even reacts very much like a one-time fifteen minutes of fame person—from stage right to frustration to wondering when the next stage (or other) appearance might happen to telling anyone who will listen about his glory days. Or for that matter, certain artists and actors who enjoyed a touch more than fifteen minutes of fame. The moment when the mice turn from major Fir Tree fans to agreeing that the Fir Tree isn’t very interesting any more is also probably all too familiar to many artists.

But—blame the current holiday season, if you wish—I can’t help reading this and reading it as a diatribe against the practice of cutting down fir trees every Christmas. Oh, sure, as the story itself notes, fir trees are cut down for a variety of reasons, with Christmas as just one of them, and as the story doesn’t acknowledge, they can also fall down from old age, or severe winds, or forest fires. And sure, this particular fir tree ends up getting used twice—once for Christmas, once for a fire—so I can’t even say that it was cut down just for one Christmas Eve night of stories, presents and lights. And this Fir Tree is not always the most sympathetic character, even when he suddenly realizes that he’s leaving his friends in the forest, or the sad moment when the rats and the mice decide he’s boring.

Still, the air of melancholy and regret that penetrates the story, not to mention the Fir Tree’s rather belated recognition that life genuinely had been good for him out in the forest, and later while listening to the story of Humpty Dumpty, rather makes me think that Andersen intended us to feel a touch of pity for Christmas trees, and maybe think about leaving them in the meadows—or these days, I suppose, Christmas tree farms—instead of bringing them into our homes.

If that was his intent, I can say it most definitely failed. If his hope was to spread Christmas cheer, it most definitely failed. But if his hope was to remind us that fame and beauty and joy can be fleeting, and thus to enjoy such things when they come—well. In that, he succeeded.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.

Hans Christian Anderson had issues. Major issues.

If we leave the trees on the Christmas tree farms, what will the families who depend on this income do?

@2

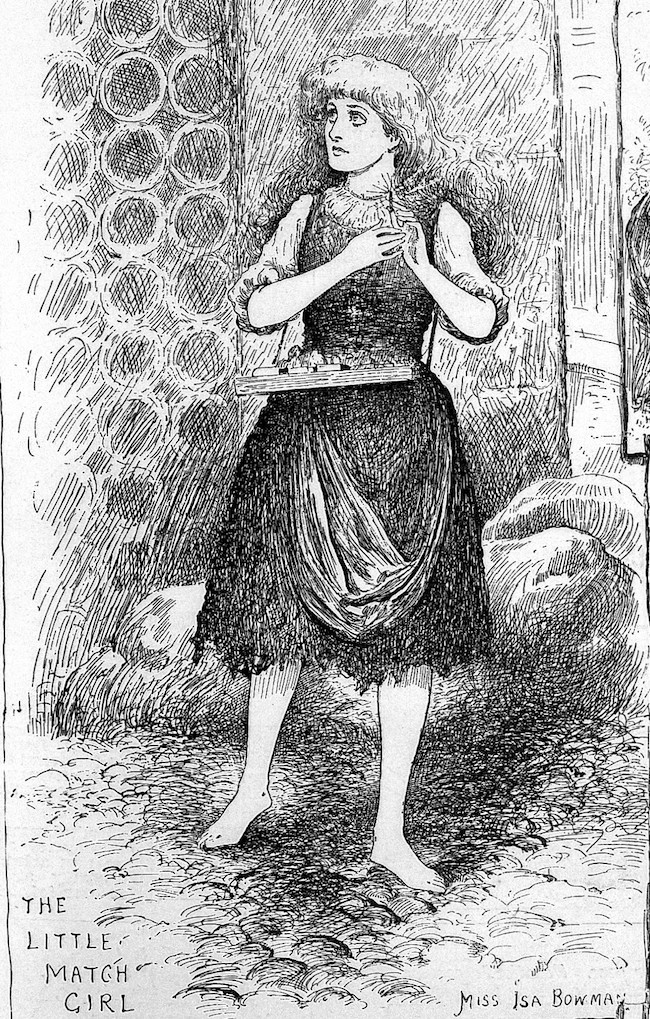

Sell matches?

@3, good one!

HCA, fairy tales by and for the clinically depressed. I really wish the poor man had lived in a time where therapy and medication were available to him. But apparently his contempoaries liked his downbeat stories. Otherwise we would never have heard of him.

@@.-@: “Otherwise we would have never heard of him.”

Funniest comment ever. Unintentionally so, I’m afraid.

I meant if his stories weren’t published and read we would never have heard of him. What did you think I meant?

Now that I think about it, HCA might have been the guy who invented grimdark…

I thought of that too. If he was alive now he’d probably be playing Warhammer.

Be careful what you ask for. You may get it.

“The Fir Tree” had a big impact on me as a kid. I loved decorating the tree and seeing it look festive but I also felt very, very sorry for it. I would sit by the tree to do my homework to keep it company. To some extent I still have those feelings as an adult. We get our trees from a local tree farm; I have come around to convince myself that those trees are grown for the purpose of being harvested – like broccoli, or kale, only much bigger! In our area, once “tree season” is over, they are chipped and used for hiking trail maintenance. Or so we’re told.

what happens to the fir tree at the end of the story ?